“This is exactly the kind of philosophical look at foraging that is needed today.”

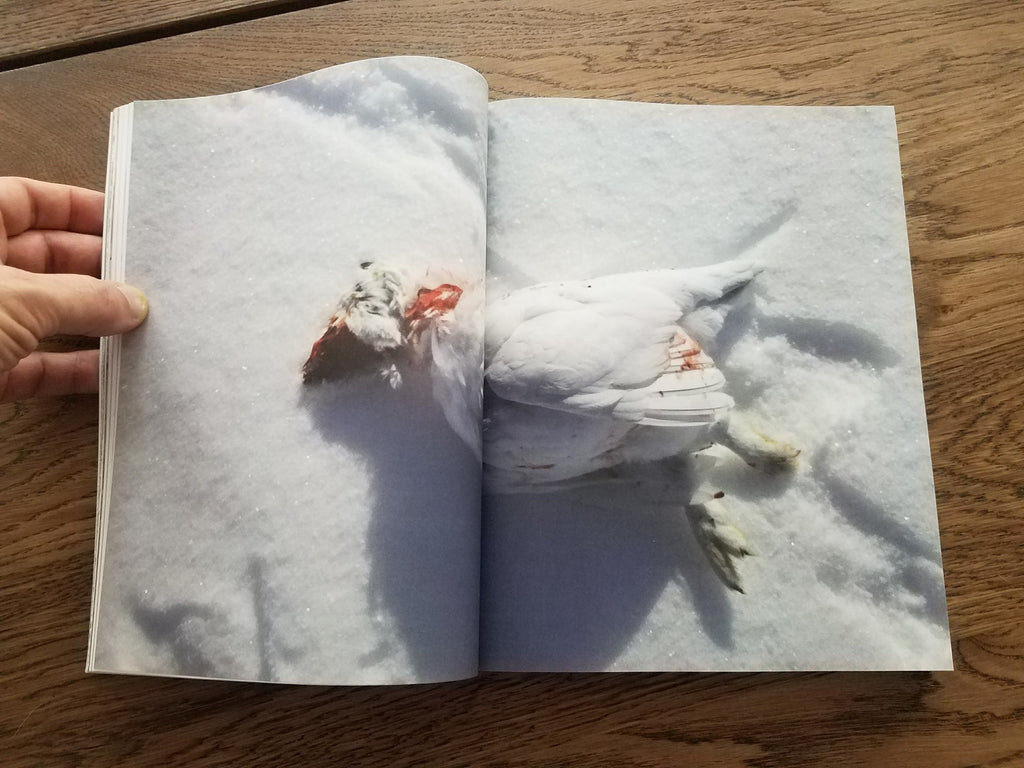

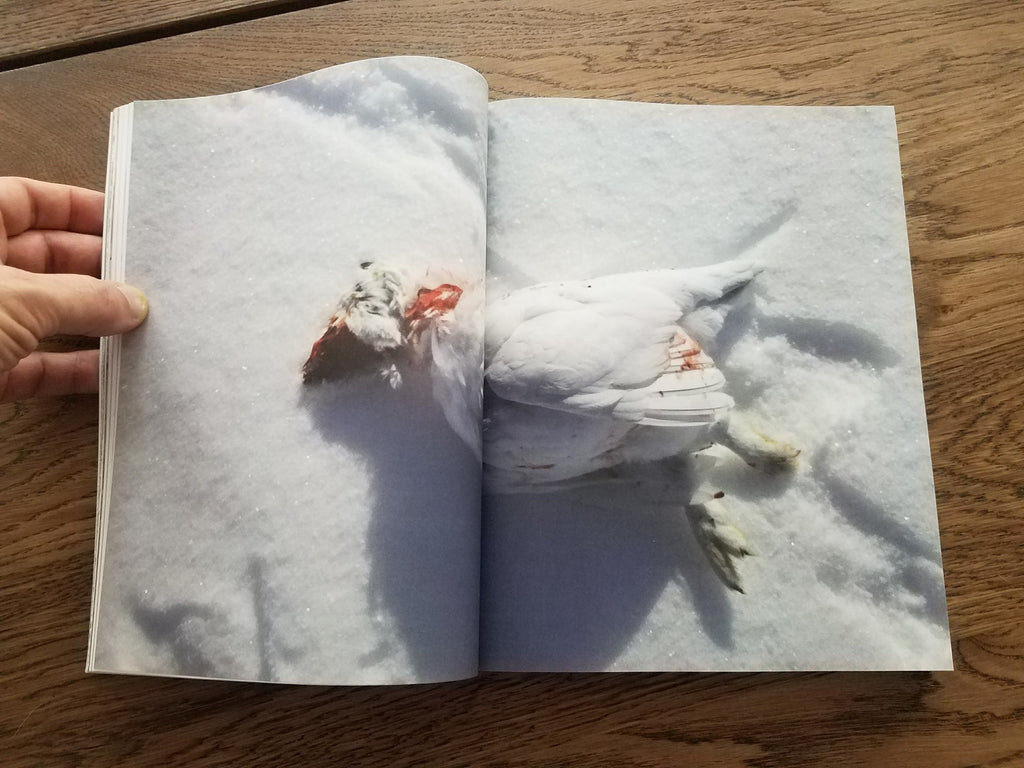

It is pretty astonishing to hear René tell us this. He had just turned off the blasting Norwegian death metal, sat down at a cheap folding table in a construction trailer perched at the edge of a wharf, out back from Noma and began to look through the Eat Your Sidewalk cookbook. René starts at the beginning flipping through the pages as we talk. After about twenty pages he gets to a double-page spread with an image of a bird -- head severed and blood seeping into the fresh snow. He gets very excited.

“This is my favorite bird to cook.” Then he pauses and looks at us.

“Do you know my favorite way to cook it?” He is turning the pages slowly as he continues to speak about this amazing bird...

OK, let's pause here for a brief moment, we just need to say a few things: prior to this meeting, we didn’t have any connection to René, nor do we have any connection to the high-end food world. We don’t jet around the globe to exotic three-star restaurants, have a fancy agent or backers with big fat wallets — our cookbook developed from a modest Kickstarter campaign a few years ago and is ultimately a labor of love and curiosity, so this moment is huge for us.

We have been working on this cookbook for the past five or so years. It has been a crazy process. Our first Kickstarter was a miserable failure. We were totally unclear about the project because we ourselves were unsure of exactly what was the bigger goal. People sensed this and it totally flopped. We regrouped, somewhat figured out what we were up to, relaunched, and it worked-- just.

The success of the Kickstarter was only the beginning — now we had to write. Writing is miserable and beautiful in equal measure. It puts you in the middle of the kind of thinking that you cannot do in your head. Sentences sit on the screen staring back at you -- asking you to rethink each word. In the hesitant act of typing and deleting each letter -- words, sentences, paragraphs and whole pages appear and disappear as concepts invent and negate themselves in a matter of minutes. This pain and discovery went on for what eventually became years. Rhizomic tangents emerged and lead us on long exploratory journeys that occasionally bore fruit and shifted the whole book. Drafts were sunk and dumped unceremoniously. We missed many deadlines and sent out many corrective notices to our backers as the many near total re-writes led us slowly to discover what the book wanted to be about.

The tangents took us to various sites from Japan, to LA to Poland to Alaska. Ultimately out of this non-linear journey what developed wasn’t anything like a traditional cookbook with recipes, precise ingredient lists, and the usual filler stories.

There was a moment in southern Japan, outside Yamaguchi, we realized that the book needed to take on a new form to accommodate the uncovering the kinds of recipes you never find in cookbooks: the recipes for the modern western mindset, as well as very basic recipes for leaving this mindset. We were on a foraging walk along an urban creek with a Shinto priest, a Buddhist monk, a geologist, a couple of ecologists, a local farmer/hunter and a regional historian. As we wandered along the creek foraging plants each spoke about the plant we were holding from different cosmological perspectives. We were all negotiating between and across worlds. The river itself was five or more distinct things, each in opposition to the other. The real was unfolding and refolding in a complex origami figure before our eyes. How could this become a book?

As this investigation led us deep into the histories and philosophies of eating, cooking and foraging we imagined that if anyone would be willing to follow us there it would be someone like René. We had read Time and Place in Nordic Cuisine years before as an experimental work of ecological philosophy. Our time in the high arctic of Alaska and Baffin Island gave us a different way of think of time and place and we were curious about how these differences could be tasted and felt directly in the recipes. We spent a lot of time debating our differences—what should show up on a plate and how? All the while we kept hearing interesting things about NOMA and what René was up to.

Fast forward a couple of years and just as we were "finishing" the book (for the fifth time) we got invited to participate in a museum exhibition and conference on the Anthropocene in Aarhus, Denmark. This was fantastic luck: here was our ticket to Denmark and NOMA! Now we had the possibility of being within a few hours of NOMA. To be honest, the exhibition and conference seemed interesting but the fee was not enough to actually cover our expenses. It was the usual art world BS (bait and switch) where we should feel so honored to be invited that we would be willing to pay… Normally we stay away from pay-to-play Ponzi schemes, but in this case, we saw a magical opportunity: what if we could detour on the way to Aarhus and "drop in" on René at NOMA in Copenhagen?

That summer we really pulled out all the stops to finish the book, Stan flew in from Austin and we met up with Matthew in New Paltz for one last massive editing session. In an empty classroom, on a dozen borrowed tables we neatly laid out every spread in the book and began to edit and re-edit everything: text, layout, design, images, diagrams, and cover. We worked through many nights and right up until the very last minute. I only finished printing out the final spreads of each page early on the morning of our flight. All the while we tried to be in contact with anyone from NOMA, but they obviously have much better things to do with their time than talk with random hacks. The day of our flight came and no luck. We were just going to have to gamble that René was even there.

That morning I met Matthew very early at JFK, after clearing security we sat down at the bar and over a few whiskeys we hand glued all the pages together of the one copy of the book in existence. Despite our best efforts, it looked big, imperfect and decidedly unprofessional. I carefully wrapped it in some brown paper and tied it into a “neat” package hoping that as the glue dried the pages would not slip or warp during the flight.

Somewhere over the middle of the Atlantic Matthew and I woke up and looked at each other.

“You know, this is really fucking crazy. We have no idea if he is even going to be there!”

“Hey, at least we get to see something of the countryside.”

“Do you even know if they are going to be open when we arrive?”

“And what are we going to say? “René, please stop everything we want to show you something?”

“He’s going to be like: “and who are you?”

“Oh shit — this is crazy…”

We just laughed hard at our naivety and the absurdity of the idea. What else could we do? It was a totally idiotic gamble. I sat in my cramped seat unable to fall back asleep thinking “what are we going to say? Even if he is there, and even if he is interested — it is absurd to think that he would have time!”

But, by now the plane was already descending through the clouds.

We arrived in Copenhagen, rented a car, realized that it was a standard, started hiccuping and stalling through the streets as Google got us blindly to the waterfront. In the thick salty fog we walked the last block to NOMA.

NOMA greets you as an unpretentious building and sign, sitting on the wharfs of a once working harbor (the luxury condos are springing up). The person at the door greeted us very cordially but with a distinct sense that we were not guests. This is probably a critical detail: we now realized we were arriving in the middle of service, which we had little choice about — between planes, ferries and when we needed to be at the exhibition — this was the only moment that would work.

“Good afternoon gentlemen, welcome to NOMA, what can I do for you?”

“Hello, thank you… We just came by to drop something off for René.”

“Sure, well, he is right behind me in the kitchen.”

Matthew and I shared a furtive glance of shock.

“You can go in”

And so we did. Now I might not be remembering this right, it has been a couple of years, maybe he first went back to check with René. I don’t remember. I do remember the attitude, it was relaxed and human: you want to talk with René? -- well go talk with him. Such a pleasant surprise and certainly not what we expected.

We found ourselves in a medium sized kitchen where René was instructing two chefs on the details of melting a fat just right. He stops and greets us. I just remember him saying:

“… I don’t have much time. Today is really busy and we have many writers and critics with us.”

I apologize and explain ourselves really briefly, “…we are ecological designers and we have just finished a philosophical cookbook on rethinking urban foraging. We totally get how busy you are and just wanted to leave a copy with you…” I am sure I said some more about where we were coming from etc. Basically, I felt bad to be imposing on him at this crazy moment. I was happy to have experienced their generosity and content to just leave the book with him and head back out. But René started to wipe his hands,

“Alright, that is interesting. Just give me one moment…” He proceeded to give some really precise and insightful guidance to his two chefs. Then he turned to us and motioned to follow him.

“We have to go out back to get any privacy, if we go up to the office, we will just get disturbed”. So we followed him out back onto the dock where there was a stack of construction trailers and cooking equipment.

“These are our fermentation labs, and upstairs is some extra office space. Let's go.”

We peer into the window of the door and he points out some of the fermentation experiments. There must have been over fifty different experiments. To our eyes, it looked like curious amateur mycologists had compressed the universe of Sandor Katz into hundreds of white buckets.

(René & Matthew looking at the experiments)

As we climb the steep stairs we can hear death metal blasting. We get inside and in the sparsely furnished space, another chef is preparing for the evening service going over lists. He turns the music down, we are introduced, and we all sit down to look over the book.

René starts at the beginning flipping through the pages as we talk. After about twenty pages he gets to a double spread image of a freshly killed winter ptarmigan. He gets very excited.

“Now this is my favorite bird to cook. It has such an interesting life...” He proceeds to tell us about it and what he finds so interesting. He is turning the pages slowly as he continues to speak. Then he pauses and looks at us.

“Do you know my favorite way to cook it?”

“It is with the self-fermented willow tips. Because it has to eat continuously in winter it stores willow tips in its throat pouch to regurgitate during the night. And in the throat pouch, they ferment. Now, these fermented willow tips have the most amazing flavor.” At which point he turns the page to a picture of us harvesting the fermented willow tips and preparing a fermented sauce.

He starts laughing and we all laugh. He looks over at us, and we say something about paying attention to what is happening -- now, amongst the laughter the conversation becomes real. The other chef joins us and we talk page by page about food, ecology, placemaking strategies, foraging, how we could approach cooking today, and how we can try new approaches to economies, ecologies, and urban life. By this point, we have pretty much gone through the book. René is stopping often as something catches his eye or we bring up a topic. After quite some time he politely explains how he better get back to things — the guests will want to meet him.

“…but before you go you need to meet up with Mikkel who heads up our larger foraging initiative. We are just about to launch a countrywide education program…” We go back inside and upstairs with René and he introduces us to Mikkel. We say our goodbyes and he says to us

“Thank you for coming by…this is exactly the kind of philosophical look at foraging that is needed today. It is really good to see.…let’s stay in touch as the book evolves” And with that, he disappears back into the kitchen.

We spent the next few hours with Mikkell talking about their project to help teach every child in Denmark to forage. We share our experiences in developing forageable landscapes, simple apps, and leading workshops. We tour the many cooking, experimenting and preparing spaces. NOMA is a big operation full of people working really hard, but in a relaxed, joyous manner — quite unlike any restaurant I had been in. Really it is much bigger and more ambitious than a restaurant. The restaurant in some sense is just one piece of the puzzle in how they imagine they can help transform much of everyday life.

We finally leave with barely enough time to catch the last ferry to the southern half of Denmark. First the obligatory picture out front:

(Matthew upon leaving NOMA)

We really had to floor it to get on the ferry. We make it and arrive long after everyone waiting for us at the museum had gone to bed. The conference turned out to be remarkable. We prepared a dinner which we served directly on the lawn so guests had to forage for both our “dishes” and plants.

Leave a comment